Richard Novak, MD is a Stanford physician board certified in anesthesiology and internal medicine.Dr. Novak is an Adjunct Clinical Professor in the Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine at Stanford University, the Medical Director at Waverley Surgery Center in Palo Alto, California, and a member of the Associated Anesthesiologists Medical Group in Palo Alto, California.

emailrjnov@yahoo.com

Latest posts by THE ANESTHESIA CONSULTANT

(see all)An inept anesthesia provider can lose a patient’s life in less than ten minutes.

NEWSPAPER HEADLINE: “ANESTHESIOLOGIST KILLS PREGNANT MOTHER DURING EMERGENCY SURGERY”

What follows is a true story, with the names changed to protect the identities of the individuals…

THE CASE: At 1:30 a.m. during the 14th month of his anesthesia training, Dr. Tony Andrews had been on duty inside the hospital since 7:00 a.m. the previous day–a total of 19 hours already. He’d spent most of that time inserting epidural anesthetics into the lower backs of laboring women on the obstetrics ward. He went to sleep in his on-call room shortly after midnight, exhausted and hopeful that he’d sleep until dawn.

No such luck. The telephone woke him up–the caller was Jennifer Rogers, an obstetrician with a busy private practice. “I need you,” she said. “I have a patient named Naomi Jordan who’s in labor with new onset of vaginal bleeding and late decels. I need to do a stat C-section.”

A layman’s translation of Jennifer’s sentence was this: Naomi Jordan was a laboring mother who was bleeding from her vagina. Her baby’s heart rate was dropping to dangerously low levels (known as decelerations, or decels) during the late phase of each uterine contraction. Dr. Rogers needed to do an emergency cesarean section, that is, she needed to cut open the lower abdomen of the mother, cut open the uterus (the medical term for the womb), and deliver the baby before the mother’s bleeding endangered the baby’s health. An emergency cesarean section meant Dr. Andrews wouldn’t get back to sleep for three hours, minimum.

“How much blood has she lost?” he mumbled, trying not to fall back asleep.

“No more than a cup so far, but the bleeding could accelerate within minutes.”

“I’ll be there in a minute.” Every cesarean section required an anesthetic–that’s why Dr. Rogers called Dr. Andrews. He was sleeping in the hospital to be immediately available for urgent obstetric anesthetics. He turned on the room light and rubbed my eyes. His wrinkled blue scrubs served as both pajamas and surgical attire. He put his sneakers back on and set out down the hallway to find his new patient.

Once Dr. Andrews was on his feet, the prospect of emergency surgery jolted him like a double espresso. By the time he reached Naomi Jordan’s room, his head was clear and he’d forgotten what time of night it was.

Naomi Jordan was a round-faced black woman in her 20’s. She was sitting up in bed and panting her way through a labor contraction. She flared her lips and bared her teeth to endure the pain and grunted out, “Ow, ow, ow,” with each exhaled breath. Naomi did little to hide her suffering, and paid no attention to Andrews when he entered the room. A gray-haired labor and delivery nurse stood at the bedside. The nurse held one hand on Naomi’s shoulder and focused her eyes on the fetal monitor screen that traced the baby’s heart rate.

Dr. Andrews opened the patient’s chart to skim through the pertinent details. Naomi was 25 years old and healthy. She was 9 months pregnant with her first child. Her current weight was 185 pounds, and she was 5 feet 4 inches tall. She’d been in labor for four hours, and her progress had been unremarkable until the last thirty minutes.

He sat down on the bed next to the patient, and said, “Hi, Ms. Jordon, I’m Dr. Andrews, one of the anesthesiologists who will be with you during your cesarean section.” What he didn’t say was, “I’m a partially-trained anesthesiologist.” It was his objective to appear confident and competent–she didn’t have to know he still had almost a year before he finished his training. She didn’t have to know that his calm appearance was a guise that hid any uncertainty due to his inexperience.

Sweat dripped down Naomi’s cheeks and forehead. Her eyes were dilated and wild. She replied, “My baby girl. I just want my baby to be all right.”

“We’ll do everything we can,” he said. “You’re going to need be asleep for the surgery. For most cesarean sections, anesthesiologists give an injection in the lady’s back–a spinal anesthetic–to numb you from your chest down. But because you’re bleeding from below, that’s not a safe option.”

“I can see my baby as soon as I wake up, right?”

“Yes you can. I’ll give you medicine into your I.V., and you’ll fall asleep in seconds. When you wake up, the surgery will be finished.” Dr. Andrews rattled through a brief explanation of the common risks, which included post-operative pain, nausea, and a sore throat from the breathing tube that I would place after she lost consciousness. “It’s common for the bleeding to stop once you’ve delivered your baby. It’s not likely that you’ll receive a blood transfusion, but if I need to give you blood to keep you safe, I will.”

She nodded her head and shivered. “I’m scared to death,” she said.

“I’m not. I’ll take good care of you.” He touched the back of her hand, and said, “I’ll be right back.”

He stepped out of her room to find a telephone. This was his second and final year of anesthesia residency training, and he was the sole anesthesiologist on the obstetrics ward at 1:40 in the morning. He had a faculty backup, Dr. Luke Harrington, who was at his home, presumably asleep. It was time to end Dr. Harrington’s slumbers.

Dr. Andrews called Dr. Harrington and explained the urgent clinical situation. Dr. Harrington said, “If she’s bleeding, she’ll need a general anesthetic. I’ll be right in.”

When patients have significant bleeding, the volume of blood in their arteries and veins is depleted. For most cesarean sections, anesthesiologists prefer to give a regional anesthetic (either a spinal anesthetic or an epidural anesthetic), that leaves the patient awake but numb from the nipples down. Neither a spinal nor an epidural can be safely administered in a patient who is actively bleeding. Spinal and epidural anesthetics relax the sympathetic nervous system and dilate both arteries and veins, lowering the blood pressure further. Dilating arteries that are already emptied because of bleeding is dangerous, and can lead to cardiac arrest or death.

Dr. Andrews hung up the phone and returned to Naomi’s bedside. The nurse was disconnecting the fetal monitors and readying the bed for transport to the operating room. Together they rolled the gurney down the hallway, and into the operating room. A surgical scrub technician and an operating room nurse were waiting for them inside the OR. The nurses and Dr. Andrews pulled surgical masks over their faces. Only Naomi Jordan stayed unmasked. Her hands shook and her voice cracked. “Is my baby still all right? She’s going to be O.K., isn’t she?”

“We’re going to move ahead and deliver her as soon as we can,” Dr. Andrews said. He hung her I.V. bottle on a pole next to the anesthesia machine and said, “Can you please move over from your bed to the operating room table?”

With a loud grunt and a louder moan, Naomi wiggled herself to her right from the hospital bed onto the narrow O.R. table. She left behind a two-foot-wide circular stain of blood on the sheets of her bed–evidence of ongoing vaginal bleeding. The sight of the pool of blood fed Dr. Andrews’ sense of urgency. It looked like more than a cup had spilled onto the sheets. How much blood had she lost?

He used his stethoscope to listen to Naomi’s chest, and confirmed that her heart tones and breath sounds were normal. He asked her to open her mouth, and assessed how easy it would be to insert a breathing tube after he anesthetized her. She had a short neck and a thick tongue, but otherwise he didn’t note anything exceptional about her mouth or airway. Dr. Andrews went about his routine and attached a blood pressure cuff to her arm, electrocardiogram stickers to her chest, and an oximeter probe to her finger.

Her heart rate was fast at 120 beats per minute. The elevated heart rate could be secondary to her anxiety, but it could be because her bleeding was ongoing and her heart was working hard to pump a depleted blood volume to her vital organs.

Her blood pressure was 100/55, a lower value than the last reading of 115/60 ten minutes earlier. The low blood pressure worried him–it could be further evidence that her blood vessels were emptying as she continued to bleed. The pulse oximeter on her finger gave a reading of 100%, indicating that her arterial blood was 100% saturated with oxygen–a good sign.

Naomi looked like she was ready to sit up and run out of the room. “It’s freezing in here,” she said, glancing around the room at the anesthesia machines and the array stainless steel surgical tools laid out on the scrub table. “I’m so scared. Can’t my mom be in here with me?”

“No,” Dr. Andrews said as he loaded my syringes with anesthetic drugs. “When patients are going to be asleep, it’s not safe for family to be in here observing. You’re going to be all right.”

The operating room nurse pulled up Naomi’s gown and began painting the bulbous abdomen with Betadine, an iodine disinfectant soap. Dr. Rogers entered the room. She was a trim, attractive woman in her thirties. She grabbed Naomi’s left hand and wiped away the tears from her patient’s eyes. “We’ll take great care of you,” she said. Naomi blinked hard and closed her eyes.

A female scrub tech unfolded a large blue sterile paper drape, and set it down over Naomi’s abdomen to cover the Betadine-painted skin. The scrub tech’s job was to hang the drapes to isolate the surgical field, and after that to hand sterile instruments to the surgeon during the surgery. She handed one edge of the drape to Andrews, and he applied clamps to secure the drape to two tall metal poles to the left and right of the patient’s shoulders. This configuration formed a wall of blue paper with Naomi’s head and the anesthesiologist on one side of the barrier, and the sterile surgical field on the opposite side. Dr. Rogers reentered the operating room. She’d left to scrub her hands, and now she donned the sterile gown and gloves of her trade. She took her position on the left side of the patient’s abdomen, and looked Dr. Andrews in the eye. “Are you ready to get her asleep?” she asked him.

“I’m still waiting for Dr. Harrington,” he said. “Otherwise I’m ready to go.” He turned to the nurse and said, “Call the general O.R. and the ICU. Find out if any other anesthesiologists are available to assist me.”

“Will do,” she said, and she picked up a phone.

It was 1:55 a.m. Dr. Andrews had checked the necessary anesthesia equipment, and it was all present and in order: breathing tubes, laryngoscopes needed for inserting a breathing tube, multiple syringes loaded with anesthetic drugs, and the anesthesia machine capable of delivering mixtures of oxygen, nitrous oxide, and the potent anesthetic vapor called isoflurane.

He looked down at the spheres of sweat beading up on Naomi’s forehead. She was breathing oxygen through a clear plastic mask. Each time she exhaled, water vapor fogged the clear plastic of the mask in front of her mouth.

The surgeon looked at the clock and said, “I don’t have any monitor of the fetal heart tones at this point, so I have no idea if the baby’s all right. The patient is still bleeding. We need to get the kid out.”

Dr. Andrews’ head was spinning. Where was Dr. Harrington? Tony Andrews was 31 years old and had been an M.D. for over five years, but he’d never been in this exact situation without a faculty anesthesiologist before. He was confident– he had plenty of medical experience. This was his second year of anesthesia residency training, and he’d administered about eight hundred anesthetics in the preceding thirteen months. He’d done dozens of general anesthetics for cesarean sections just like this one, but he’d never done one alone. He was nervous as hell, but was he certain that he could handle starting this case without Dr. Harrington in attendance? The problem was . . . it was too risky to wait any longer. The baby’s life was at stake. The mother’s life was at stake.

The nurse interrupted his train of thoughts. “The main O.R. has two fresh trauma patients,” she said. “They don’t have any extra anesthesiologists to come up and help you. And the ICU phone is busy.”

Dr. Andrews inhaled a big breath and blew it out through pursed lips. He could think of no other alternative. “O.K., I’m going ahead,” he said to the surgeon. She nodded in affirmation.

“I need you to give the patient cricoid pressure as she goes to sleep,” Dr. Andrews said to the operating room nurse. Cricoid pressure is a medical maneuver whereby an assistant presses down firmly on a specific spot on the patient’s anterior neck, called the cricoid cartilage. This action compresses the patient’s esophagus below. Compressing the esophagus prevents regurgitation of stomach contents into the throat and mouth. The stomach of a pregnant woman empties slowly, and the anesthesiologist must assume the stomach is full of undigested food. Regurgitated vomit in the patient’s airway and lungs can be lethal.

The letters A-B-C, abbreviations for the words Airway-Breathing-Circulation, summarize the management of every acute medical situation. As soon as Naomi went to sleep and couldn’t breathe on her own, she needed an airway tube. That’s the anesthesiologist’s job–Dr. Andrews was the only one in the operating room with the training and ability to insert the endotracheal tube.

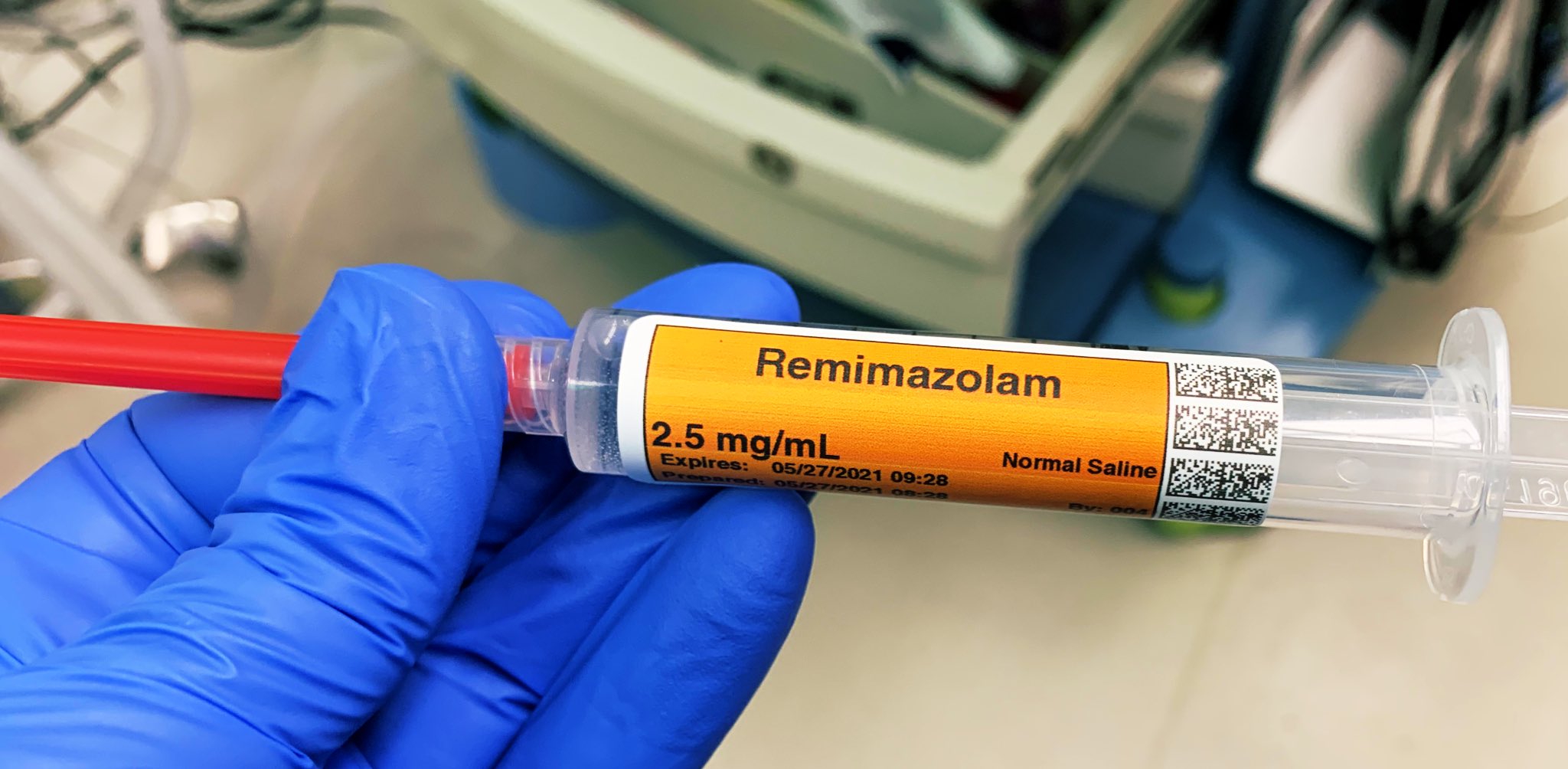

He injected 20 milliliters of the hypnotic drug sodium pentothal into her I.V. over a three-second span of time, and then injected 4 milliliters of the muscle-paralyzing drug succinylcholine.

“You’re doing great. Everything’s going to be all right,” he said to Naomi, a wish as much as a promise. The nurse located the cricoid cartilage on Naomi’s neck, and pressed downward.

Sodium pentothal is a rapid-acting drug that induces unconsciousness. Naomi’s eyes closed ten seconds after the injection. The second drug, succinylcholine, also known as “sux,” is an ultra fast-acting muscle relaxant. Intravenous sux renders all the muscles in the body flaccid within a minute. This paralysis makes it possible for the anesthesiologist to insert a lighted instrument called a laryngoscope into a patient’s mouth, visualize the vocal cords in the patient’s larynx (the medical name for the voice box), and place a hollow breathing tube through the vocal cords into the trachea (the medical name for the windpipe). The paralysis also makes it impossible for the patient to breathe on her own.

The operating room was quiet except for the beeping of Naomi’s pulse on my monitoring equipment. Everyone was waiting for Dr. Andrews. Surgery could not begin until he inserted the breathing tube.

Thirty seconds after he injected the sux, every muscle of Naomi’s body began to shiver in involuntary paroxysms. The widespread contraction-then-paralysis of every skeletal muscle of Naomi’s body is a phenomenon known as fasciculation, a well-known and expected side effect of sux. Watching an otherwise motionless patient fasciculate is a creepy experience–the patient’s body moves as if demon forces were tunneling beneath the surface of the skin.

Once the fasciculation ceased, Dr. Andrews knew his patient was paralyzed. His heart thundered as he removed her oxygen mask. He turned on the light on my laryngoscope and gripped the metal handle in his left fist. After she fell asleep, Naomi’s lips and tongue collapsed against each other, obstructing any view of her teeth or inside her mouth. Dr. Andrews first job was to pry the mouth open and insert the lighted metal laryngoscope blade between her incisors. He followed the light as it illuminated her mouth and throat. He was looking for the pearly white vocal cords that guarded the windpipe. His initial search was futile–all he could see were the flabby pink tissues of her tongue and throat. He pulled harder the laryngoscope handle in an effort to lever open the airway, but he still saw nothing but pink flesh. He began to breathe faster, and sweat poured from his underarms.

At that moment, Dr. Andrews heard the sound that strikes terror into every anesthesiologist’s heart–a descending musical scale keeping time with every one of Naomi’s heartbeats.

The descending musical notes came from the medical monitoring device known as a pulse oximeter. The pulse oximeter is the most vital and important monitor in any acute care medical setting. The pulse oximeter records its signal from a clip placed across the tip of a patient’s finger. One side of the clip is a red light emitting diode (LED), and the other side of the clip is a receptor that quantifies the amount of red light that passes through the patient’s fingertip. A computer in the pulse oximeter filters out all the signals except for red light that pulsates. The only source for pulsating red light in the fingertip is blood in the small arteries. The pulse oximeter converts red hue of the pulsating arterial blood to a percentage of oxygen saturation in the blood, based on how red the blood is:

More oxygen in the blood => redder blood => an increased oxygen saturation of 90% or greater => the patient is safe.

Less oxygen => darker purple blood => an oxygen saturation lower than 90% => the patient’s life is in danger.

The pulse oximeter emits a beep tone with every measured heartbeat. As Naomi’s oxygen saturation declined below 90%, the beeping note decreased in pitch. As her lips turned blue before his eyes, the descending chromatic scale of the pulse oximeter announced that the blood in her fingertip contained less oxygen. This also meant her heart and brain were receiving less oxygen.

At the same time, the rate of the oximeter beeps increased to over 130 beats per minute. Dr. Andrews’ own heart rate was higher than Naomi’s. Naomi Jordon and her baby were dying in his hands, and it was up to him to step it up and save her. It was up to Dr. Andrews to insert the breathing tube.

Instead, he panicked.

He repeated the same futile attempts to visualize her vocal cords. He reinserted the same metal laryngoscope into her mouth and followed the illuminated trail of its flashlight bulb. He was still looking for the two pearly white vocal cords and the blackness of the tracheal lumen between them.

Instead, all he saw were folds of pink tissues.

The menacing notes of the oximeter beeps descended further. The patient was out of oxygen. Dr. Andrews pushed the metal laryngoscope deeper into her throat in a desperation move to find the trachea.

“Can’t you intubate her?” Dr. Rogers asked.

Dr. Andrews was too stuck in his predicament to answer. The pulse oximeter tone was deeper than he’d ever heard it. He glanced up at the machine, and saw that the oxygen saturation was in the 50’s.

Incompatible with life.

I’ve killed her, he thought, and the vivid image of a newspaper headline filled his head: “ANESTHESIOLOGIST KILLS PREGNANT MOTHER DURING EMERGENCY SURGERY.” At that second, Dr. Tony Andrews would have given anything to escape from that mess with Naomi Jordon alive and well.

Stupefied by failure, he didn’t know what else to do except to keep trying over and over to put the tube in.

THE RESCUE: At that moment, Dr, Tony Andrews’ luck turned. The outer door to the operating room opened, and Dr. Luke Harrington ran in, wearing the non-surgical attire of blue jeans and a faded blue polo shirt. Street clothes were never allowed in the sterile confines of an operating room. Dr. Harrington observed the chaotic scene through the operating room window that faced in from the outside hallway, and figured out there was no time for a wardrobe change.

Instead of screaming at me or asking questions, Dr. Harrington said, “Take the laryngoscope out of her mouth NOW. Let’s put the anesthesia mask back over her face.”

Dr. Andrews complied.

“Hold the mask with two hands,” he said. “Fit it in a good seal over her face, and I’ll squeeze the ventilation bag.”

Dr. Andrews pressed the clear plastic mask over her mouth and nose and held it in an airtight fashion, with one hand at 3 o’clock and one hand at 9 o’clock over each of her cheeks. Dr. Harrington squeezed the ventilation bag, and by this technique they were able to force 100% oxygen through her upper airway into her lungs via bag-mask ventilation.

Of course, Dr. Andrews thought. She was dying and turning blue. I was supposed to stop the futile attempts to put in a breathing tube, and just do this. Pump in oxygen via the facemask.

Dr. Andrews held his breath and looked up at the vital sign monitors. Her oxygen saturation hung low, still in the 60’s. Dangerously low.

His mouth was so dry that he couldn’t swallow.

Dr. Harrington remained impassive. If he was worried, he wasn’t showing it. He fixed his eyes on the oximeter numerical readout.

For the next sixty seconds Dr. Andrews’ mind echoed, God, please, God please. . . . A full minute went by, and then note-by-note the beep tone of the oximeter rose in pitch, and the numeric readout climbed in parallel. From 60%, the oxygen saturation rose to 66%, . . . 72%, . . . 83%, then 93%.

They’d done it! With an oxygen saturation greater than 90%, her brain and heart were now receiving an adequate supply of oxygen. The surgeon peered over the drapes at us. She was still holding her scalpel dormant. She couldn’t start the cesarean section until the anesthesiologists had safely placed the endotracheal tube.

Dr. Harrington asked Dr. Andrews, “What happened when you tried to intubate her?”

“I couldn’t see anything but pink tissues.”

Dr. Harrington lifted the mask away from her face, and opened her mouth to look inside. He frowned and nodded. “Let’s change her head position. Get me two white towels.”

He had Dr. Andrews lift up Naomi’s shoulders, while he stuffed two folded white towels behind her neck. Naomi Jordan’s head extended backwards and her mouth fell open for the first time.

“Looks better. Try it again,” Dr. Harrington said. Dr. Andrews was surprised that he’d want him try again, since he’d done nothing right so far. He wondered why Dr. Harrington didn’t just take over.

The patient’s oxygen saturation was up to 100%. Dr. Harrington pushed another 10-milliliter bolus of sodium pentothal into the IV to keep Naomi asleep, and Dr. Andrews opened her mouth to try again. This time, as he advanced the laryngoscope blade and light into her mouth, the anatomical landmarks were more obvious. Past the base of her tongue, he located the epiglottis, the pink flap of tissue that closed off the windpipe each time she swallowed. He was elated–he hadn’t seen any recognizable structures my last time in. The larynx, the gateway to the trachea, lay just beneath the epiglottis. Since neither light nor vision can travel in a curve, he needed to lift up the epiglottis to see past it. He pulled hard on the laryngoscope handle toward the ceiling. To his relief and amazement, he saw the black hole of the tracheal opening.

“I’ve got it,” Dr. Andrews said, his voice cracking.

“Here’s the tube,” Dr. Harrington said, as he handed Dr. Andrews the clear plastic endotracheal tube. Dr. Andrews fed the tube through her mouth, past the epiglottis and into the trachea. Dr. Harrington injected 8 milliliters of air from an empty syringe into a portal on the tube. This inflated a balloon near the distal tip of the tube, which formed a seal against the inner walls of Naomi’s trachea.

Dr. Harrington connected the endotracheal tube to the hoses from the anesthesia machine, and squeezed the ventilation bag. The patient’s chest expanded. Dr. Andrews pressed his stethoscope against her chest and listened. The breath sounds were prominent and conclusive. The endotracheal tube was in the correct place.

“You can cut,” Dr. Harrington said to the surgeon.

Dr. Rogers turned her attention to the patient’s lower abdomen, and made a swift horizontal incision above the pubic bone. Her assistant retracted the tissue layers as Dr. Rogers cut deeper inside the body. Within five minutes, she’d controlled all the bleeding and exposed the anterior wall of the uterus. A second incision cleaved the womb, and she reached inside to pull the baby out. Within 30 seconds, she’d delivered the baby, cut the umbilical cord, and handed the baby off to the team of pediatricians ready to resuscitate her.

The anesthesiologists’ work wasn’t over after they placed the breathing tube. They turned on a mixture of 50% nitrous oxide in 50% oxygen, and dialed in a 0.6% mixture of the anesthetic gas isoflurane. These gases would keep Naomi asleep as the surgeon worked to sew her back together.

Across the room the pediatricians ventilated the baby with oxygen by mask. Within 5 minutes the baby was pink and crying. “Apgar scores are 2 and 9,” the pediatric resident said. The Apgar score is a rating from 0 to 10, calculated one minute after birth and again at 5 minutes, used to quantify how healthy and vital the baby is. The score is a sum of 0 – 2 points each for five different criteria, including Activity, Pulse, Grimace, Appearance, and Respirations. The baby’s 5 minute Apgar score of 9 was nearly a perfect 10, and a sign that the baby had survived the birthing process without apparent harm.

Dr. Andrews thanked Dr. Harrington for his timely arrival. Dr. Andrews’ hands were still shaking, supercharged with the adrenaline that had poured into his system over the last hectic hour.

Sixty minutes later, the surgeon closed the last surgical incision, concluding the cesarean section. Dr. Andrews turned off the anesthetic gases. Naomi Jordan opened her eyes, and Dr. Andrews removed the breathing tube.

“Is my baby girl here?” she asked.

“She’s right here,” Dr. Andrews said, and the pediatrician handed the infant to her mother. Naomi cried tears of joy. It was all Dr. Andrews could do to keep from crying along with her.

Dr. Harrington had rescued all three of them: Naomi, her baby daughter, and Tony Andrews.

LESSONS LEARNED: The Naomi Jordan story highlights three key issues: 1) the crucial importance of airway management, 2) surgery and anesthesia have risk, and(3) the problem of inexperienced anesthesia practitioners performing medical care they are not fully capable to handle.

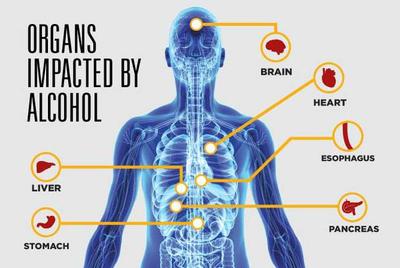

(1) The crucial importance of airway management: Losing control of an unconscious patient’s airway is a hazard that every anesthetist dreads, every day, in every operating room. Indeed, the most important skill an anesthesia provider learns is not how to administer powerful sleep drugs, but how to keep patients alive and well under the influence of powerful sleep drugs. All major anesthetic drugs and gases cause profound depression of breathing and/or cardiac function.

Keeping the anesthetized patient’s airway open via a mask or a laryngeal mask airway or a breathing tube is a critical skill for every anesthesia provider. If the airway closes, the brain is deprived of oxygen. Irreversible brain damage can occur after as little as four minutes without oxygen.

(2) The risks involved in surgery and anesthesia: Deep down, every surgical patient has the same worry: How safe is surgery and anesthesia?

Methods of evaluating anesthetic mortality are inexact and controversial. In 1999 the Institute of Medicine published their report entitled To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health Care System. In this report, the Committee on Quality of Health Care in America stated that, “anesthesia is an area in which very impressive improvements in safety have been made.” The Committee cited anesthesia mortality rates that decreased from 1 death per 5,000 anesthetics administered during the 1980s, to 1 death per 200,000-300,000 anesthetics administered in 1999. Keep in mind that this statistic reflects the frequency of all patients, healthy or ill, who die in the operating room.

This conclusion that anesthesia mortality has plummeted is not universal. When mortality is defined as any death occurring within 48 hours following surgery, the statistics are much different. In 2002, anesthesiologist Dr. Robert S. Lagasse of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York published a study in Anesthesiology, the specialty’s leading journal, that challenged the Institute of Medicine report.

Lagasse presented data on surgical mortality from two academic New York hospitals between the years 1992 and 1999. Mortality was defined as any death occurring within 48 hours following surgery. There were 351 deaths in 184,472 surgeries–an overall surgical mortality rate of 1 death per 532 cases. Keep in mind that these were deaths within 48 hours–not deaths in the operating room.

Deaths related to anesthesia errors were much less–only 14 deaths out of 184,472 surgeries–a rate of 1 death per 13,176 cases. Lagasse’s anesthesia-related mortality rate of 1 per 13,176 surgeries was significantly different that the Institute of Medicine’s rate of 1 death per 200,000-300,000 surgeries. Lagasse wrote, “We must dispel the myth that anesthesia-related mortality has improved by an order of magnitude. Science does not support this claim.”

Lagasse compared anesthesia to the aviation industry: “The safety of airline travel, for example, has increased dramatically in this century, but since the 1960s there has been minimal improvement in fatality rates. This may be due to the effect that improved safety technology has had on air traffic density. Technology has made it possible to meet production pressures of the commercial airline industry by allowing more takeoffs and landings with less separation between aircraft. With this increased aircraft density comes increased danger, thereby offsetting potential improvements in safety. This may be analogous to the practice of anesthesiology in which improvements in medical technology have led to increased anesthetic management of older patients with significantly more concurrent disease.”

Today’s surgery patients are sicker than ever. About 5% of all surgical patients die within one year of surgery. For patients over the age of 65 years, 10% of all surgical patients die within one year of surgery.

Naomi Jordan was healthy, and a cesarean section is a common surgical procedure. But her case was an emergency procedure, and general anesthesia for cesarean section is known to be a high risk for airway problems because pregnant women have narrowed upper airways, decreased oxygen reserves, and stomachs that do not empty normally. A 2003 study showed that a difficult or failed intubation following induction of general anesthesia for cesarean section was the number-one factor in anesthesia-related maternal complications.

Because of this, the use of general anesthesia for cesarean sections has declined. In a Harvard study published in 1998, only 3.6% to 7.2% of cesarean sections were done under general anesthesia. Difficult intubations were frequently unexpected, as was the case for Naomi Jordan, and one failed intubation resulted in the mother’s death.

Whenever possible, the safest anesthetic choice for cesarean section is a spinal or an epidural block, in which the anesthetist injects a local anesthetic drug via a needle inserted in the low back area. This numbs the mother from her nipples to her toes, and she stays awake and breathes on her own during surgery.

(3) Inexperienced anesthesia practitioners performing medical care they are not fully capable to handle: During the first twelve months of a physician’s anesthesia residency, each trainee is closely mentored and restricted to easier surgeries if possible. Each year in July, new residents enter each residency program and existing residents are advanced from first-year residents to second-year residents, while second year residents become third-year residents. Each July, every anesthesia trainee faces a new tier of responsibilities and more challenging cases. The Naomi Jordan case occurred in August, when Dr. Tony Andrews was inexperienced and less than two months into the more challenging second year of residency. In a teaching hospital, July and August are the least desirable months to be a patient.

Within a few years of Dr. Andrews’ incident, the hospital he trained at changed its staffing, and made it mandatory that an anesthesia faculty member stayed in the hospital all night. Inexperienced residents would never be called on to handle emergencies alone–a good idea that grew out of the Naomi Jordan case and others. In addition, the American Board of Anesthesiology added an additional year of required training to all anesthesiologist residencies, so every anesthesiologist left their residency with a minimum of three years of training post-internship instead of just two.

Prior to the Naomi Jordan case, Dr. Andrews was both inexperienced and cocky–a bad combination. He screwed up the management of her airway, but Dr. Harrington rescued him, and the outcome was excellent. If Dr. Andrews had harmed Naomi Jordan, he would have been known as the anesthesiologist that bumped off a healthy patient. Despite his previous 800 uneventful anesthetics up to that night, he would be remembered for the one that went bad. The Naomi Jordan case taught Dr. Andrews a lesson he never forgot. While he never lost control of another patient’s airway in his years of anesthesia practice after the Jordan case, that wasn’t the lesson he learned. The lesson Dr. Andrews learned was a lesson every anesthesia provider eventually comes to accept:

You’re only as good as your last anesthetic

The most popular posts for laypeople on The Anesthesia Consultant include:

How Long Will It Take To Wake Up From General Anesthesia?

Why Did Take Me So Long To Wake From General Anesthesia?

Will I Have a Breathing Tube During Anesthesia?

What Are the Common Anesthesia Medications?

How Safe is Anesthesia in the 21st Century?

Will I Be Nauseated After General Anesthesia?

What Are the Anesthesia Risks For Children?

The most popular posts for anesthesia professionals on The Anesthesia Consultant include:

10 Trends for the Future of Anesthesia

Should You Cancel Anesthesia for a Potassium Level of 3.6?

12 Important Things to Know as You Near the End of Your Anesthesia Training

Should You Cancel Surgery For a Blood Pressure = 178/108?

Advice For Passing the Anesthesia Oral Board Exams

What Personal Characteristics are Necessary to Become a Successful Anesthesiologist?

*

*

*

*

Published in September 2017: The second edition of THE DOCTOR AND MR. DYLAN, Dr. Novak’s debut novel, a medical-legal mystery which blends the science and practice of anesthesiology with unforgettable characters, a page-turning plot, and the legacy of Nobel Prize winner Bob Dylan.

KIRKUS REVIEW

In this debut thriller, tragedies strike an anesthesiologist as he tries to start a new life with his son.

Dr. Nico Antone, an anesthesiologist at Stanford University, is married to Alexandra, a high-powered real estate agent obsessed with money. Their son, Johnny, an 11th-grader with immense potential, struggles to get the grades he’ll need to attend an Ivy League college. After a screaming match with Alexandra, Nico moves himself and Johnny from Palo Alto, California, to his frozen childhood home of Hibbing, Minnesota. The move should help Johnny improve his grades and thus seem more attractive to universities, but Nico loves the freedom from his wife, too.

Hibbing also happens to be the hometown of music icon Bob Dylan. Joining the hospital staff, Nico runs afoul of a grouchy nurse anesthetist calling himself Bobby Dylan, who plays Dylan songs twice a week in a bar called Heaven’s Door. As Nico and Johnny settle in, their lives turn around; they even start dating the gorgeous mother/daughter pair of Lena and Echo Johnson. However, when Johnny accidentally impregnates Echo, the lives of the Hibbing transplants start to implode. In true page-turner fashion, first-time novelist Novak gets started by killing soulless Alexandra, which accelerates the downfall of his underdog protagonist now accused of murder. Dialogue is pitch-perfect, and the insults hurled between Nico and his wife are as hilarious as they are hurtful: “Are you my husband, Nico? Or my dependent?”

The author’s medical expertise proves central to the plot, and there are a few grisly moments, as when “dark blood percolated” from a patient’s nostrils “like coffee grounds.” Bob Dylan details add quirkiness to what might otherwise be a chilly revenge tale; we’re told, for instance, that Dylan taught “every singer with a less-than-perfect voice…how to sneer and twist off syllables.” Courtroom scenes toward the end crackle with energy, though one scene involving a snowmobile ties up a certain plot thread too neatly. By the end, Nico has rolled with a great many punches.

Nuanced characterization and crafty details help this debut soar.

Click on the image below to reach the Amazon link to The Doctor and Mr. Dylan:

Learn more about Rick Novak’s fiction writing at ricknovak.com by clicking on the picture below:

Like this:

Like Loading...

An astronaut en route to Mars develops severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A fellow crew member examines him and finds significant tenderness and guarding in the right lower quadrant of his abdomen. The crew members teleconference with physicians on Earth, with a 20-minute communication delay because of the 140-million mile distance between them. The physicians confirm a probable diagnosis of appendicitis. Because the spaceship is more than 200 days away from Earth, the physicians instruct the crew to proceed with surgery and anesthesia in outer space.

An astronaut en route to Mars develops severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. A fellow crew member examines him and finds significant tenderness and guarding in the right lower quadrant of his abdomen. The crew members teleconference with physicians on Earth, with a 20-minute communication delay because of the 140-million mile distance between them. The physicians confirm a probable diagnosis of appendicitis. Because the spaceship is more than 200 days away from Earth, the physicians instruct the crew to proceed with surgery and anesthesia in outer space.

/90038143-56a46dca3df78cf7728260d8.jpg?w=788&ssl=1)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/what-to-expect-from-cannabis-withdrawal-22304_FINAL-5c38d2c1c9e77c0001f9ba1b.png?w=788&ssl=1)

Sublingual sufentanil is approved for use only in medical settings, for the treatment of moderate to severe acute pain. But it is also possible that sublingual sufentanil will become the most dangerous street opiate ever known. This column reviews the arrival of sublingual sufentanil, from the viewpoint of a practicing anesthesiology attending.

Sublingual sufentanil is approved for use only in medical settings, for the treatment of moderate to severe acute pain. But it is also possible that sublingual sufentanil will become the most dangerous street opiate ever known. This column reviews the arrival of sublingual sufentanil, from the viewpoint of a practicing anesthesiology attending.

This is a handheld tool with a camera on one end and a video screen on the other. The video laryngoscope allows the physician to see around the curves of a large man’s tongue and jaw, and to visualize the opening to the windpipe without moving or extending the cervical spine (which in some football injuries must be suspected of having an unstable fracture). I’m certain that modern day RSI equipment at NFL games includes not only a portable videoscope but also a larger array of breathing tubes and airway management tools such as you’d find in a difficult airway cart in an operating room or an emergency room. The American Society of Anesthesiologists

This is a handheld tool with a camera on one end and a video screen on the other. The video laryngoscope allows the physician to see around the curves of a large man’s tongue and jaw, and to visualize the opening to the windpipe without moving or extending the cervical spine (which in some football injuries must be suspected of having an unstable fracture). I’m certain that modern day RSI equipment at NFL games includes not only a portable videoscope but also a larger array of breathing tubes and airway management tools such as you’d find in a difficult airway cart in an operating room or an emergency room. The American Society of Anesthesiologists

PubMed is most important medical website on the Internet.

PubMed is most important medical website on the Internet.

CLINICAL CASE: You’re scheduled to anesthetize a healthy 55-year-old female for an appendectomy. Her blood pressure is 150/90 on admission. In the operating room, you induce anesthesia with your standard recipe of 2 mg of midazolam, 100 mcg of fentanyl, 200 mg of propofol, and 40 mg of rocuronium, and intubate the trachea. Five minutes after induction and 15-30 minutes before the surgical incision will occur, her blood pressure drops to 85/45. Is this a problem? What will you do? What level of hypotension is acceptable to you?

CLINICAL CASE: You’re scheduled to anesthetize a healthy 55-year-old female for an appendectomy. Her blood pressure is 150/90 on admission. In the operating room, you induce anesthesia with your standard recipe of 2 mg of midazolam, 100 mcg of fentanyl, 200 mg of propofol, and 40 mg of rocuronium, and intubate the trachea. Five minutes after induction and 15-30 minutes before the surgical incision will occur, her blood pressure drops to 85/45. Is this a problem? What will you do? What level of hypotension is acceptable to you?

A patient infected with the Ebola virus is admitted to your hospital’s intensive care unit. You are called to intubate the Ebola patient for respiratory failure. What do you do?

A patient infected with the Ebola virus is admitted to your hospital’s intensive care unit. You are called to intubate the Ebola patient for respiratory failure. What do you do?